Operation Meetinghouse Do It Again Lemay

On the night of nine/x March 1945, the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) conducted a devastating firebombing raid on Tokyo, the Japanese capital urban center. This attack was code-named Operation Meetinghouse by the USAAF and is known every bit the Great Tokyo Air Raid in Japan.[ane] Bombs dropped from 279 Boeing B-29 Superfortress heavy bombers burned out much of eastern Tokyo. More than 90,000 and perhaps over 100,000 Japanese people were killed, mostly civilians, and ane million were left homeless, making it the most subversive single air attack in man history. The Japanese air and ceremonious defenses proved largely inadequate; 14 American aircraft and 96 airmen were lost.

The assault on Tokyo was an intensification of the air raids on Japan which had begun in June 1944. Prior to this operation, the USAAF had focused on a precision bombing campaign against Japanese industrial facilities. These attacks were mostly unsuccessful, which contributed to the decision to shift to firebombing. The operation during the early hours of 10 March was the get-go major firebombing raid confronting a Japanese urban center, and the USAAF units employed significantly different tactics from those used in precision raids, including bombing past dark with the aircraft flight at depression altitudes. The all-encompassing destruction caused past the raid led to these tactics condign standard for the USAAF's B-29s until the end of the war.

There has been a long-running debate over the morality of the 10 March firebombing of Tokyo. The raid is often cited every bit a key instance in criticism of the Allies' strategic bombing campaigns, with many historians and commentators arguing that it was non acceptable for the USAAF to deliberately target civilians, and other historians stating that the USAAF had no choice just to modify to area bombing tactics given that the precision bombing campaign had failed. It is generally acknowledged that the tactics used confronting Tokyo and in similar subsequent raids were militarily successful. The attack is commemorated at two official memorials, several neighborhood memorials, and a privately run museum.

Background [edit]

Pre-war USAAF doctrine emphasized the precision bombing of key industrial facilities over area bombing of cities. Early American strategic bombing attacks on Germany used precision tactics, with the bomber crews seeking to visually place their targets. This proved difficult to accomplish in practice. During the last 20 months of the war in Europe, non-visual attacks accounted for well-nigh half of the American strategic bombing campaign against Federal republic of germany. These included major area bombing raids on Berlin and Dresden, also every bit attacks on several towns and cities conducted every bit part of Operation Clarion.[two] The American attacks on Germany mainly used high-explosive bombs, with incendiary bombs bookkeeping for only 14 percent of those dropped by the Eighth Air Force.[3] The British Bomber Command focused on destroying German language cities from early on 1942 until the end of the state of war, and incendiaries represented 21 percent of the tonnage of bombs its aircraft dropped.[4] Area bombing of German cities by Allied forces resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of civilians and massive firestorms in cities such as Hamburg and Dresden.[5]

A B-29 dropping conventional bombs over Japan. The bombs are beingness scattered by the wind, a common occurrence which fabricated precision bombing difficult.

Japanese forces conducted area bombing attacks on Chinese cities throughout the state of war.[6] Few attempts were made to target industrial facilities, with the goal of the campaign being to terrorize civilians and cut the Chinese forces off from their sources of supplies. Chongqing, China's provisional capital, was ofttimes attacked by aircraft using incendiary and high explosive bombs. These raids destroyed most of the metropolis.[7]

The American Doolittle Raid on eighteen April 1942 was the starting time air attack on Tokyo, but inflicted lilliputian harm on the city.[8] In June 1944 the USAAF's 20 Bomber Control began a campaign against Nippon using B-29 Superfortress bombers flight from airfields in China. Tokyo was beyond the range of Superfortresses operating from Communist china, and was not attacked.[9] This changed in October 1944, when the B-29s of the XXI Bomber Command began moving into airfields in the Mariana Islands. These islands were close enough to Nippon for the B-29s to comport a sustained bombing campaign against Tokyo and virtually other Japanese cities.[9] The first Superfortress flight over Tokyo took place on 1November, when a reconnaissance aircraft photographed industrial facilities and urban areas in the western districts of the metropolis.[10] [11] The remainder of Tokyo was photographed in subsequent reconnaissance flights, and these images were used to plan the 10 March raid and other attacks on urban areas.[12]

The overall plan for the strategic bombing campaign against Japan specified that it would embark with precision bombing raids against key industrial facilities, and subsequently include firebombing attacks on cities.[xiii] The first target directive issued to the XXI Bomber Command by its parent unit, the Twentieth Air Strength, on 11 November, 1944 specified that the principal target was Japanese aircraft and aviation engine factories. These targets were to be attacked by precision bombing. Japanese cities were specified as the secondary target, with surface area bombing being authorized for use against them. The directive also indicated that firebombing raids were likely to exist ordered against cities to test the effectiveness of this tactic.[14] The Twentieth Air Forcefulness had an unusual command structure, as it was personally headed by General Henry H. Arnold, the commanding officer of the USAAF.[fifteen]

B-29 raids on Tokyo commenced on 24 Nov. The first raid targeted an aircraft engine mill on the city's outskirts, and acquired lilliputian damage.[9] XXI Bomber Command'due south subsequent raids on Tokyo and other cities mainly used precision bombing tactics and high explosive bombs, and were largely unsuccessful due to agin conditions weather and a range of mechanical problems which affected the B-29s.[9] These failures led to the caput of the Control being relieved in January 1945. Major Full general Curtis LeMay, the commander of Xx Bomber Control, replaced Full general Hansell.[9] Arnold and the Twentieth Air Force's headquarters regarded the entrada against Japan up to that fourth dimension as unsuccessful, and LeMay understood that he would as well be relieved if he failed to deliver results. He believed that changing the accent from precision bombing to area bombing was the most promising option to plough the XXI Bomber Control's performance around.[sixteen]

Preparations [edit]

Early incendiary raids on Japan [edit]

USAAF planners began assessing the feasibility of a firebombing campaign against Japanese cities in 1943. Nippon'due south main industrial facilities were vulnerable to such attacks equally they were concentrated in several large cities, and a high proportion of production took identify in homes and small factories in urban areas. The planners estimated that incendiary bomb attacks on Japan's half dozen largest cities could crusade physical damage to nigh xl percent of industrial facilities and result in the loss of vii.six one thousand thousand man-months of labor. It was also estimated that these attacks would impale over 500,000 people, render about 7.75 million homeless and strength nearly 3.5 one thousand thousand to be evacuated.[17] [eighteen] The plans for the strategic bombing offensive against Nihon developed in 1943 specified that it would transition from a focus on the precision bombing of industrial targets to area bombing from around halfway in the campaign, which was forecast to be in March 1945.[xix]

Preparations for firebombing raids confronting Japan began well before March 1945. In 1943 the USAAF tested the effectiveness of incendiary bombs on adjoining High german and Japanese-style domestic building complexes at the Dugway Proving Ground.[xx] [21] These trials demonstrated that M69 incendiaries were particularly effective at starting uncontrollable fires. These weapons were dropped from B-29s in clusters, and used napalm as their incendiary filler. After the bomb struck the basis, a fuse ignited a charge which first sprayed napalm from the weapon, and and so ignited it.[22] Prior to March 1945, stockpiles of incendiary bombs were built upwardly in the Mariana Islands. These were accumulated on the basis of XXI Bomber Command plans which specified that the B-29s would each carry 4 brusque tons (three.6 t) of the weapons on twoscore percent of their monthly sorties.[23] Arnold and the Air Staff wanted to look to use the incendiaries until a big-scale program of firebombing could be mounted, to overwhelm the Japanese city defenses.[24]

Several raids were conducted to test the effectiveness of firebombing against Japanese cities. A small incendiary attack was made against Tokyo on the night of 29/30 November 1944, but caused little damage. Incendiaries were also used equally role of several other raids.[25] On xviii Dec 84 Twenty Bomber Command B-29s conducted an incendiary raid on the Chinese urban center of Hankou which caused extensive damage.[26] That day, the Twentieth Air Force directed XXI Bomber Command to dispatch 100 B-29s on a firebombing raid against Nagoya. An initial attack took identify on 22 December which was directed at an shipping factory and involved 78 bombers using precision bombing tactics. Few of the incendiaries landed in the target area.[25] On 3January, 97 Superfortresses were dispatched to firebomb Nagoya. This set on started some fires, which were shortly brought nether control past firefighters. The success in countering the raid led the Japanese authorities to go over-confident well-nigh their power to protect cities confronting incendiary attacks.[27] The next firebombing raid was directed confronting Kobe on 4February, and bombs dropped from 69 B-29s started fires which destroyed or damaged 1,039 buildings.[28]

On 19 Feb the Twentieth Air Strength issued a new targeting directive for XXI Bomber Command. While the Japanese aviation industry remained the principal target, the directive placed a stronger accent on firebombing raids confronting Japanese cities.[29] The directive also called for a big-scale trial incendiary raid as before long equally possible.[30] This attack was made against Tokyo on 25 February. A total of 231 B-29s were dispatched, of which 172 arrived over the city; this was XXI Bomber Command's largest raid up to that time. The attack was conducted in daylight, with the bombers flying in formation at loftier altitudes. It acquired extensive damage, with almost 28,000 buildings being destroyed. This was the most subversive raid to have been conducted against Japan, and LeMay and the Twentieth Air Force judged that it demonstrated that large-calibration firebombing was an constructive tactic.[31] [32]

The failure of a precision bombing attack on an aircraft factory in Tokyo on 4March marked the finish of the period in which XXI Bomber Command primarily conducted such raids.[33] Civilian casualties during these operations had been relatively depression; for example, all the raids against Tokyo prior to x March acquired one,292 deaths in the metropolis.[34] [35]

Preparations to assault Tokyo [edit]

In early March, LeMay judged that further precision bombing of Japanese industrial targets was unlikely to be successful due to the prevailing weather atmospheric condition over the land. In that location were on boilerplate but 7 days of clear skies each calendar month, and an intense jet stream made it hard to aim bombs from high altitudes. Due to these constraints, LeMay decided to focus XXI Bomber Control's attacks on Japanese cities.[36] While he fabricated this decision on his own initiative, the full general directions issued to LeMay permitted such operations.[37] On fiveMarch XXI Bomber Command's personnel were advised that no farther major attacks would be scheduled until 9March. During this period LeMay'southward staff finalized plans for the attack on Tokyo.[38] At a coming together on 7March, LeMay agreed to carry an intense series of raids against targets on the island of Honshu betwixt 9and 22 March as part of the preparations for the invasion of Okinawa on 1Apr.[39]

LeMay decided to adopt radically dissimilar tactics for this entrada. Analysis by XXI Bomber Command staff of the 25 February raid concluded that the incendiary bombs had been dropped from likewise loftier an distance, and attacking at lower levels would both improve accuracy and enable the B-29s to carry more bombs.[Note 1] This would likewise expose them to the Japanese air defenses, but LeMay judged that poor Japanese fire command tactics meant that the additional gamble was moderate.[41] Equally weather conditions over Japan tended to exist more favorable at night and the LORAN systems the B-29s used to navigate were more effective after dusk, it was also decided to conduct the attack at night.[42] This led to a decision to direct the shipping to attack individually rather than in formations every bit it was non possible for the B-29s to keep station at night. Flight individually would also lead to reductions in fuel consumption as the pilots would non need to constantly accommodate their engines to remain in formation. These fuel savings allowed the Superfortresses to carry twice their usual bomb load.[43] USAAF intelligence had adamant that the Japanese had simply 2 night fighter units, and these were believed to pose little threat. As a result, LeMay decided to remove all of the B-29s' guns other than those at the rear of the shipping to reduce the weight of the aircraft and farther heave the weight of bombs they could carry.[42] [44] [45] While LeMay made the ultimate decision to adopt the new tactics, he acknowledged that his plan combined ideas put forwards by many officers.[46] On 7March, some of the B-29 crews flew training missions in which they practiced using radar to navigate and attack a target from depression altitude. The airmen were not told the purpose of this preparation.[47]

The officers who commanded XXI Bomber Command's three flight wings agreed with the new tactics, just there were fears that they could consequence in heavy casualties.[42] These concerns were shared by some of LeMay's staff. XXI Bomber Control'south intelligence officers predicted that 70 percentage of the bombers could exist destroyed.[48] LeMay consulted Arnold's chief of staff Brigadier General Lauris Norstad about the new tactics, but did non formally seek approval to prefer them. He later justified this action on the grounds that he had wanted to protect Arnold from blame had the attack been a failure.[44] LeMay notified the Twentieth Air Force headquarters of his intended tactics on 8March, a day he knew Arnold and Norstad would exist absent. At that place is no show that LeMay expected that the Twentieth Air Force would object to firebombing civilian areas, but he may accept been concerned that it would have judged that the new tactics were too risky.[49]

Japanese defenses [edit]

The Japanese military anticipated that the USAAF would make major night attacks on the Tokyo region. After several pocket-sized night raids were conducted on the region during Dec 1944 and January 1945, the Majestic Japanese Army Air Strength's 10th Air Partition, which was responsible for intercepting attacks on the Kantō region, placed a greater emphasis on grooming its pilots to operate at night. One of the partitioning's flying regiments (the 53rd Air Regiment) was also converted to a specialized night fighter unit.[50] On the dark of 3/4 March, the Japanese armed services intercepted American radio signals which indicated that the XXI Bomber Command was conducting a major dark flying practice. This was interpreted to mean that the forcefulness was preparing to start large-calibration dark raids on Japan.[51] Withal, the Japanese did non wait the Americans to modify to low altitude bombing tactics.[52]

The military forces assigned to protect Tokyo were insufficient to finish a major raid. The Eastern District Army's Kanto Air Defense Sector was responsible for the air defense of the Tokyo region, and was accorded the highest priority for shipping and antiaircraft guns.[53] [Note 2] The 1st Antiaircraft Division controlled the antiaircraft guns stationed in the key region of Honshu, including Tokyo. It was made upwards of 8 regiments with a full of 780 antiaircraft guns, as well every bit a regiment equipped with searchlights.[55] American military intelligence estimated that 331 heavy and 307 light antiaircraft guns were allocated to Tokyo's defenses at the time of the raid.[56] A network of lookout boats, radar stations and picket posts was responsible for detecting incoming raids.[57] Due to shortages of radar and other fire command equipment, Japanese antiaircraft gunners found it difficult to target aircraft operating at nighttime.[58] The radar stations had a short range and burn control equipment for the antiaircraft batteries was unsophisticated.[59] Every bit of March 1945, almost of the tenth Air Sectionalization'southward 210 combat aircraft were 24-hour interval fighters, with the 53rd Air Regiment operating 25 or 26 nighttime fighters.[60] The regiment was experiencing difficulties converting to the night fighter function, which included an overly intensive preparation program that wearied its pilots.[61]

Tokyo's civil defenses were also lacking. The urban center'due south burn down department comprised around 8,000 firemen spread between 287 fire stations, simply they had lilliputian modern firefighting equipment.[62] The firefighting tactics used by the fire department were ineffective against incendiary bombs.[63] Civilians had been organized into more than 140,000 neighborhood firefighting associations with a nominal force of 2.75 one thousand thousand people, but these were besides ill-equipped.[64] The basic equipment issued to the firefighting associations was incapable of extinguishing fires started by M69s.[63] Few air raid shelters had been constructed, though almost households dug crude foxholes to shelter in well-nigh their homes.[65] Firebreaks had been created beyond the metropolis in an endeavor to stop the spread of fire; over 200,000 houses were destroyed every bit role of this effort. Rubble was ofttimes not cleared from the firebreaks, which provided a source of fuel. The Japanese Authorities also encouraged children and civilians with non-essential jobs to evacuate Tokyo, and 1.7 million had departed by March 1945.[66] However, many other civilians had moved into Tokyo from impoverished rural areas over the aforementioned period.[67]

Set on [edit]

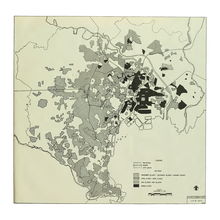

A map showing the areas of Tokyo that were destroyed during Earth State of war Two. The area burned out during the raid on nine/10 March is marked in black.

Divergence [edit]

On 8 March, LeMay issued orders for a major firebombing set on on Tokyo the next night.[68] The raid was to target a rectangular area in northeastern Tokyo designated Zone I by the USAAF which measured approximately 4 miles (6.4 km) by iii miles (4.viii km). This area was divided by the Sumida River, and included most of Asakusa, Honjo and Fukagawa Wards.[69] These wards formed part of the informally divers Shitamachi district of Tokyo, which was mainly populated by working-grade people and artisans.[lxx] With a population of around 1.1 one thousand thousand, it was 1 of the most densely populated urban areas in the world.[71] Zone I contained few militarily significant industrial facilities, though there were a large number of minor factories which supplied Japan'south war industries. The area was highly vulnerable to firebombing, as most buildings were constructed from woods and bamboo and were closely spaced.[52] Due to this vulnerability, information technology had suffered extensive damage and heavy casualties from fires caused by the 1923 Bully Kantō earthquake. The United States' intelligence services were aware of how vulnerable the region remained to fire, with the Office of Strategic Services rating it as containing the most combustible districts in Tokyo.[72]

The orders for the raid issued to the B-29 crews stated that the main purpose of the attack was to destroy the many small factories located inside the target area, but too noted that it was intended to cause noncombatant casualties as a means of disrupting product at major industrial facilities.[73] Each of XXI Bomber Command's three wings was allocated a different altitude to bomb from, in bands between 5,000 feet (i,500 m) and seven,000 anxiety (two,100 thou). These altitudes were calculated to be too loftier for the light Japanese antiaircraft guns to accomplish, and below the constructive range of the heavy antiaircraft guns.[56]

LeMay was unable to pb the raid in person as he had been prohibited from placing himself in a situation where he could be captured after being briefed on the development of atomic bombs.[44] Instead, the assault was led by the 314th Bombardment Wing's commanding officer, Brigadier General Thomas S. Power.[74] LeMay considered Power to be the all-time of the wing commanding officers.[75] The new tactics which were to be used in the operation were not well received past many airmen, who believed that it was safer to flop from loftier altitudes and preferred to retain their defensive guns.[45] Leaving behind the unneeded gunners also troubled many of the airmen, as bomber crews typically had a very close human relationship.[76]

In grooming for the attack, XXI Bomber Command'southward maintenance staff worked intensively over a 36-hour menstruation to fix as many aircraft as possible. This effort proved successful, and 83 per centum of the B-29s were bachelor for action compared to the average serviceability charge per unit of 60 percent. Other ground coiffure loaded the aircraft with bombs and fuel.[77] A total of 346 B-29s were readied. The 73rd Bombardment Wing contributed 169 B-29s and the 313th Bombardment Wing 121; both units were based on Saipan. At the time of the raid the 314th Bombardment Wing was arriving at Guam in the Marianas, and able to provide only 56 B-29s.[44] The B-29s in the squadrons which were scheduled to arrive over Tokyo get-go were armed with M47 bombs; these weapons used napalm and were capable of starting fires which required mechanized firefighting equipment to command. The bombers in the other units were loaded with clusters of M69s.[68] The 73rd and 313th Flop Wings' Superfortresses were each loaded with 7 short tons (6.4 t) of bombs. Equally the 314th Bombardment Wing'south B-29s would have to fly a greater distance, they each carried v short tons (4.v t) of bombs.[56]

The assault force began departing its bases at 5:35 pm local fourth dimension on 9March. It took ii and three quarter hours for all of the 325 B-29s which were dispatched to take off.[52] [56] Turbulence was encountered on the flight to Japan, but the weather over Tokyo was expert. There was picayune cloud cover, and visibility was good for the first bomber crews to arrive over Tokyo; they were able to run into conspicuously for ten miles (16 km).[52] Conditions on the footing were cold and windy, with the city experiencing gusts of betwixt 45 miles per hour (72 km/h) and 67 miles per hour (108 km/h) blowing from the southeast.[78] [79]

The first B-29s over Tokyo were iv aircraft tasked with guiding the others in. These Superfortresses arrived over the urban center shortly before midnight on 9March. They carried extra fuel, additional radios and XXI Bomber Command'southward best radio operators instead of bombs, and circled Tokyo at an altitude of 25,000 anxiety (vii,600 m) throughout the raid. This tactic proved unsuccessful, and was later on judged to have been unnecessary.[eighty]

Over Tokyo [edit]

The attack on Tokyo commenced at 12:08 am local time on ten March.[81] Pathfinder bombers simultaneously approached the target area at correct angles to each other. These bombers were manned by the 73rd and 313th Bombardment Wings' best crews.[three] Their M47 bombs apace started fires in an X shape, which was used to straight the attacks for the residual of the force. Each of XXI Bomber Command's wings and their subordinate groups had been briefed to attack different areas inside the Ten shape to ensure that the raid caused widespread damage.[82] As the fires expanded, the American bombers spread out to attack unaffected parts of the target expanse.[52] Ability'due south B-29 circled Tokyo for 90 minutes, with a squad of cartographers who were assigned to him mapping the spread of the fires.[83]

A USAAF reconnaissance photograph of Tokyo taken on 10 March 1945. Function of the area destroyed past the raid is visible at the bottom of the epitome.

The raid lasted for approximately two hours and forty minutes.[84] Visibility over Tokyo decreased over the course of the raid due to the extensive smoke over the city. This led some American aircraft to bomb parts of Tokyo well exterior the target area. The heat from the fires also resulted in the final waves of aircraft experiencing heavy turbulence.[56] Some American airmen also needed to use oxygen masks when the odor of burning flesh entered their aircraft.[85] A total of 279 B-29s attacked Tokyo, dropping 1,665 brusque tons (1,510 t) of bombs. Some other 19 Superfortresses which were unable to attain Tokyo struck targets of opportunity or targets of last resort.[86] These aircraft turned back early due to mechanical problems or pilots deciding to abort the main mission because they were agape of being killed.[87]

Tokyo's defenders were expecting an assail, but did not detect the American force until information technology arrived over the city. The air defense units in the Kanto Plain area had been placed on alert, but the nighttime fighter units were instructed not to sortie any aircraft until an incoming raid was detected.[88] While sentinel boats spotted the attack force, poor radio reception meant that most of their reports were not received. Due to disorganization in the defence force commands, petty activeness was taken on the scattered reports which came in from the boats.[78] At around midnight on 9March a small number of B-29s were detected most Katsuura, but were thought to be conducting reconnaissance flights. Subsequent sightings of B-29s flying at low levels were not taken seriously, and the Japanese radar stations focused on searching for American aircraft operating at their usual high altitudes.[89] The first alarm that a raid was in progress was issued at 12:xv am, but after the B-29s began dropping bombs on Tokyo.[81] The 10th Air Division sortied all of its available night interceptors, and the 1st Anti aircraft Sectionalization's searchlight and anti shipping units went into action.[89]

As expected by LeMay, the defense of Tokyo was not effective. Many American units encountered considerable anti aircraft fire, only it was generally aimed at altitudes either above or below the bombers and reduced in intensity over time as gun positions were overwhelmed past fires.[ninety] Still, the Japanese gunners shot down 12 B-29s. A farther 42 were damaged, of which 2 had to be written off.[91] The Japanese fighters were ineffective; their pilots received no guidance from radar stations and the efforts of the anti shipping gunners and fighter units were not coordinated.[92] No B-29s were shot down by fighters, and the American airmen reported only 76 sightings of Japanese fighters and 40 attacks by them over the course of the raid.[xc] Several Japanese pilots were killed when their aircraft ran out of fuel and crashed.[93] V of the downed B-29s managed to ditch in the sea, and their crews were rescued by Us Navy submarines.[90] American casualties were 96 airmen killed or missing, and half dozenwounded or injured.[94]

The surviving B-29s arrived back at their bases in the Mariana Islands between vi:10 and eleven:27 am local time on 10 March.[86] Many of the bombers were streaked with ashes from the fires their crews had caused.[85]

On the ground [edit]

Widespread fires apace developed beyond northeastern Tokyo. Inside 30 minutes of the start of the raid the state of affairs was across the burn department's control.[95] An hour into the raid the burn down department abandoned its efforts to stop the conflagration.[62] Instead, the firemen focused on guiding people to safety and rescuing those trapped in called-for buildings.[96] Over 125 firemen and 500 civil guards who had been assigned to help them were killed, and 96 fire engines destroyed.[62]

Driven by the strong wind, the large numbers of small fires started by the American incendiaries chop-chop merged into major blazes. These formed firestorms which quickly avant-garde in a northwesterly direction and destroyed or damaged almost all the buildings in their path.[97] [98] The merely buildings which survived the burn down were constructed of stone.[99] By an 60 minutes afterward the start of the set on most of eastern Tokyo either had been destroyed or was being affected by fires.[100]

Civilians who stayed at their homes or attempted to fight the fire had virtually no chance of survival. Historian Richard B. Frank has written that "the central to survival was to grasp chop-chop that the situation was hopeless and flee".[97] Before long later the showtime of the raid news broadcasts began advising civilians to evacuate equally quickly equally possible, but non all did so immediately.[101] The foxholes which had been dug near almost homes offered no protection against the firestorm, and civilians who sheltered in them were burned to expiry or died from suffocation.[63]

Charred remains of Japanese civilians afterwards the raid

Thousands of the evacuating civilians were killed. Families frequently sought to remain with their local neighborhood associations, but it was easy to become separated in the conditions.[102] Few families managed to stay together throughout the nighttime.[103] Escape often proved impossible, as fume reduced visibility to just a few feet and roads were speedily cut by the fires.[99] [102] Crowds of civilians oft panicked every bit they rushed towards the perceived safety of canals, with those who fell beingness crushed to death.[104] The bulk of those killed in the raid died while trying to evacuate.[105] In many cases entire families were killed.[97] One of the most deadly incidents occurred when the total bomb load of a B-29 landed in a crowd of civilians crossing the Kototoi Span over the Sumida River causing hundreds of people to exist burned to death.[106]

Few places in the targeted expanse provided safety. Many of those who attempted to evacuate to the big parks which had been created equally refuges against fires following the 1923 Smashing Kantō earthquake were killed when the conflagration moved across these open spaces.[107] Similarly, thousands of people who gathered in the grounds of the Sensō-ji temple in Asakusa died.[108] Others sheltered in solid buildings, such as schools or theatres, and in canals.[107] These were not proof against the firestorm, with smoke inhalation and heat killing big numbers of people in schools.[109] Many of the people who attempted to shelter in canals were killed by fume or when the passing firestorm sucked oxygen out of the area.[84] However, these bodies of water provided safety to thousands of others.[95] The burn down finally burned itself out during mid-morning on 10 March, and came to a stop when information technology reached big open areas or the Nakagawa Culvert.[90] [110] Thousands of people injured in the raid died over the following days.[111]

After the raid, civilians across Tokyo offered help to the refugees.[34] Firemen, police officers and soldiers also tried to rescue survivors trapped under collapsed buildings.[112] Many refugees who had previously lived in slums were accommodated in prosperous parts of the city. Some of these refugees resented the differences in living conditions, prompting riots and looting.[113] Refugee centers were also established in parks and other open areas.[114] Over a million people left the metropolis in the following weeks, with more than than 90 percentage being accommodated in nearby prefectures.[34] Due to the extent of the impairment and the exodus from Tokyo, no attempt was made to restore services to large sections of the city.[105]

Aftermath [edit]

Casualties [edit]

The charred body of a woman who was carrying a child on her back

Estimates of the number of people killed in the bombing of Tokyo on 10 March differ. Afterwards the raid, 79,466 bodies were recovered and recorded. Many other bodies were not recovered, and the metropolis's director of health estimated that 83,600 people were killed and some other 40,918 wounded.[34] [95] The Tokyo fire department put the casualties at 97,000 killed and 125,000 wounded, and the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department believed that 124,711 people had been killed or wounded. Afterward the war, the United States Strategic Bombing Survey estimated the casualties as 87,793 killed and twoscore,918 injured. The survey besides stated that the majority of the casualties were women, children and elderly people.[98] Frank wrote in 1999 that historians generally believe that at that place were between 90,000 and 100,000 fatalities, merely some fence that the number was much college.[34] For instance, Edwin P. Hoyt stated in 1987 that 200,000 people had been killed and in 2009 Mark Selden wrote that the number of deaths may have been several times the estimate of 100,000 used by the Japanese and United States Governments.[112] [115] Every bit of 2011, the Tokyo Memorial Hall honored 105,400 people killed in the raid, the number of people whose ashes are interred in the building or were claimed by their family. As many bodies were non recovered, the number of fatalities is higher than this number.[116] The big population movements out of and into Tokyo in the period before the raid, deaths of unabridged communities and destruction of records mean that it is not possible to know exactly how many died.[34]

Most of the bodies which were recovered were buried in mass graves without existence identified.[34] [117] [118] Many bodies of people who had died while attempting to shelter in rivers were swept into the sea and never recovered.[119] Attempts to collect bodies ceased 25 days after the raid.[105]

The raid also acquired widespread destruction. Constabulary records show that 267,171 buildings were destroyed, which represented a quarter of all buildings in Tokyo at the time. This destruction rendered i,008,005 survivors homeless.[95] Most buildings in the Asakusa, Fukagawa, Honjo, Jōtō and Shitaya wards were destroyed, and seven other districts of the city experienced the loss of around half their buildings. Parts of some other 14 wards suffered harm. Overall, 15.eight square miles (41 km2) of Tokyo was burned out.[120] The number of people killed and area destroyed was the largest of whatsoever single air raid of Earth War II, including the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki,[95] when each raid is considered by itself. The casualties and harm acquired by the raid and absence past workers in Tokyo considerably disrupted the Japanese war economy.[121] [122]

Reactions [edit]

LeMay and Arnold considered the operation to take been a significant success on the basis of reports made past the airmen involved and the extensive damage shown in photographs taken past reconnaissance aircraft on 10 March.[94] [123] Arnold sent LeMay a congratulatory bulletin which stated that "this mission shows your crews take the guts for anything".[111] The aircrew who conducted the attack were also pleased with its results.[124] A mail-strike assessment past XXI Bomber Command attributed the scale of impairment to the firebombing existence concentrated on a specific area, with the bombers attacking inside a brusque timeframe, and the strong winds present over Tokyo.[125]

Few concerns were raised in the United states of america during the war nigh the morality of the ten March attack on Tokyo or the firebombing of other Japanese cities.[126] These tactics were supported past the majority of decision-makers and American civilians. Historian Michael Howard has observed that these attitudes reflected the limited options to end the war which were bachelor at the time.[127] For instance, both Arnold and LeMay regarded the 10 March raid and subsequent firebombing operations equally being necessary to salve American lives by bringing the state of war to a rapid decision.[128] President Franklin D. Roosevelt probably also held this view.[129] While Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson was aware of LeMay's tactics and troubled by the lack of public reaction in the United States to the firebombing of Tokyo, he permitted these operations to keep until the finish of the war.[130]

The raid was followed by similar attacks against Nagoya on the night of 11/12 March, Osaka in the early hours of 14 March, Kobe on 17/18 March and Nagoya again on 18/19 March.[131] An unsuccessful dark precision raid was likewise conducted against an aircraft engine mill in Nagoya on 23/24 March. The firebombing attacks ended just because XXI Bomber Control'south stocks of incendiaries were exhausted.[132] The attacks on Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka and Kobe during March burned out over 31 square miles (fourscore kmtwo) of the cities.[131] The number of people killed in Nagoya, Osaka and Kobe were much lower than those in 10 March attack on Tokyo with fewer than 10,000 fatalities in each operation. The lower casualties were, in function, the result of better preparations by the Japanese authorities which had resulted from a realization that they had greatly under-estimated the threat posed by firebombing.[133]

The Japanese authorities initially attempted to suppress news of the extent of the 10 March raid, but after used it for propaganda purposes. A communique issued past the Regal Headquarters on 10 March stated that only "diverse places inside the city were set afire".[134] However, rumors of the devastation chop-chop spread across the land.[135] In a suspension from the usual practice of downplaying the impairment acquired by air attacks, the Japanese Authorities encouraged the media to emphasize the extensive scale of the destruction in an attempt to motivate acrimony against the United States.[136] Stories almost the assail were on the front page of all Japanese newspapers on 11 March. Reporting focused on the perceived immorality of the attack and the number of B-29s which had been destroyed.[137] Subsequent newspaper reports made little reference to the scale of casualties, and the few photos which were published showed little physical damage.[138] When the Japanese Government's official broadcaster Radio Tokyo reported the attack it was labeled "slaughter bombing".[95] Other radio broadcasts focused on B-29 losses and the claimed desire of Japanese civilians to go along the war.[139] American newspaper reports focused on the physical harm to Tokyo, made piddling reference to casualties and did not include estimates of the death toll. This resulted from the content of USAAF communiques and reports rather than censorship.[140]

The attack considerably damaged the morale of Japanese civilians, with information technology and the other firebombing raids in March convincing most that the war situation was worse than their government had admitted. The Japanese Government responded with a combination of repression, including heavy penalties for people accused of disloyalty or spreading rumors, and a propaganda campaign focused on restoring confidence in the country's air and civil defence measures. These measures were generally unsuccessful.[141]

Few steps were taken to improve Tokyo's defenses later the raid. The majority of the 10th Air Division'due south senior officers were sacked or reassigned every bit punishment for the unit'southward failure on 10 March.[142] Only 20 aircraft were sent to Tokyo to reinforce the tenth Air Division, and these were transferred elsewhere 2 weeks later on when no farther attacks were fabricated against the capital.[93] From Apr, the Japanese reduced their attempts to intercept Allied air raids to preserve aircraft to contest the expected invasion of Japan. The 1st Antiaircraft Sectionalisation remained active until the end of the war in August 1945.[143] The Japanese war machine never developed acceptable defenses confronting night air raids, with the dark fighter force remaining ineffective and many cities non being protected by antiaircraft guns.[144]

Between April and mid-May XXI Bomber Control mainly focused on attacking airfields in southern Japan in back up of the invasion of Okinawa. From 11 May until the terminate of the state of war the B-29s conducted day precision bombing attacks when weather conditions were favorable, and dark firebombing raids confronting cities at all other times.[145] Further incendiary attacks were conducted against Tokyo, with the final taking place on the night of 25/26 May.[146] By this fourth dimension, 50.8 percent of the urban center had been destroyed and more than than 4meg people left homeless. Further heavy bomber raids against Tokyo were judged to not be worthwhile, and it was removed from XXI Bomber Command'south target listing.[117] [147] Past the end of the war, 75 percent of the sorties conducted by XXI Bomber Command had been part of firebombing operations.[146]

Remembrance [edit]

The Dwelling of Remembrance memorial in Yokoamicho Park

Following the war the bodies which had been buried in mass graves were exhumed and cremated. The ashes were interred in a charnel house located in Sumida's Yokoamicho Park which had originally been established to hold the remains of 58,000 victims of the 1923 earthquake. A Buddhist service has been conducted to marker the ceremony of the raid on x March each year since 1951. A number of small neighborhood memorials were also established across the affected area in the years afterward the raid.[148] 10 March was designated Tokyo Peace Day by the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly in 1990.[149]

Few other memorials were erected to commemorate the attack in the decades afterward the war.[150] Efforts began in the 1970s to construct an official Tokyo Peace Museum to marking the raid, but the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly canceled the project in 1999.[151] Instead, the Dwelling of Remembrance memorial to civilians killed in the raid was built in Yokoamicho Park. This memorial was defended in March 2001.[152] The citizens who had been most active in campaigning for the Tokyo Peace Museum established the privately funded Center of the Tokyo Raids and War Damage, which opened in 2002.[151] [153] As of 2015, this heart was the master repository of data in Japan nigh the firebombing raids.[154] A pocket-sized section of the Edo-Tokyo Museum also covers the air raids on Tokyo.[155] The academic Cary Karacas has stated that a reason for the depression-profile official commemoration of the set on in Nihon is that the regime does not want to acknowledge "that it was Nihon who initiated the first-e'er air raids on Asia's cities". Karacas argues that the Japanese Government prefers to focus on the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki every bit commemoration of these attacks "reinforces the Japanese-as-victim stereotype".[155]

In 2007 a group of survivors of the 10 March raid and bereaved families launched a lawsuit seeking compensation and an amends for the Japanese Government'due south deportment regarding the set on. Every bit part of the case, information technology was argued that the raid had been a war crime and the Japanese Government had acted wrongly past agreeing to elements of the 1951 Treaty of San Francisco which waived the right to seek compensation for such actions from the Us Government. The plaintiffs also claimed that the Japanese Government had violated the post-state of war constitution by compensating the war machine victims of the raid and their families, but not civilians. The Japanese Regime argued that it did not have an obligation to compensate the victims of air raids. In 2009 the Tokyo Commune Court found in favor of the government.[156] Since that time, a public entrada has advocated for the Japanese Regime to pass legislation to provide compensation to civilian survivors of the raid.[155]

Historiography [edit]

Many historians take stated that the 10 March raid on Tokyo was a military success for the Us, and marked the start of the almost effective catamenia of air raids on Japan. For instance, the USAAF official history judged that the attack fully met LeMay'southward objectives, and it and the subsequent firebombing raids shortened the war.[157] More than recently, Tami Davis Biddle noted in The Cambridge History of the 2nd World War that "the Tokyo raid marked a dramatic plough in the American air campaign in the Far East; following on the heels of many months of frustration, it loosed the total weight of American industrial might on the faltering Japanese".[158] Marker Lardas has written that 10 March operation was simply the second genuinely successful raid on Nippon (later an attack confronting an aircraft factory on nineteen January), and "LeMay's conclusion to switch from precision battery to surface area incendiary missions and to conduct the incendiary missions from low altitudes" was the most important factor in the eventual success of the strategic bombing entrada.[159]

The Center of the Tokyo Raids and War Damage

Historians have also discussed the significance of the raid in the USAAF's transition from an emphasis on precision bombing to area bombing. Conrad C. Crane has observed that "the resort to fire raids marked some other stage in the escalation towards total war and represented the culmination of trends begun in the air state of war against Germany".[160] Kenneth P. Werrell noted that the firebombing of Japanese cities and the diminutive bomb attacks "have come to epitomize the strategic bombing campaign against Nihon. All else, some say, is a prelude or tangential".[161] Historians such as Biddle, William Westward. Ralph and Barrett Tillman have argued that the decision to change to firebombing tactics was motivated past Arnold and LeMay'due south desire to bear witness that the B-29s were constructive, and that a strategic bombing strength could be a war-winning armed services arm.[162] [163] [164] British historian Max Hastings shares this view, and has written that the circumstances in which XXI Bomber Command shifted to area attacks in 1945 mirrored those which led Bomber Command to do the aforementioned from 1942.[165]

Similar the bombing of Dresden, the bombing of Tokyo on x March 1945 is used every bit an example by historians and commentators who criticize the ethics and practices of the Centrolineal strategic bombing campaigns.[166] Concerns initially raised regarding these ii raids in the years afterward Globe War II have over time evolved into widely-held doubts over the morality and effectiveness of the campaigns.[167] For instance, Selden argues that the attack on Tokyo marked the beginning of an American "approach to warfare that targets entire populations for annihilation".[168] Every bit part of his full general critique of Centrolineal surface area bombing raids on High german and Japanese cities, the philosopher A. C. Grayling judged that the 10 March raid was "unnecessary and disproportionate".[169] Some commentators believe that racism motivated the decision to use firebombing tactics, in dissimilarity to the USAAF's greater emphasis on precision bombing in its air campaign confronting Germany.[170] Werrell has written that while racism may have influenced this, "many other factors were involved, which, I would submit, were more significant".[76] Frank has reached similar conclusions. He also argues that the USAAF would accept used firebombing tactics in Europe had German cities been as vulnerable to fire equally Japanese cities were and intelligence on the High german war economy been as defective as information technology was on the Japanese war production facilities.[171] Tillman has written that expanse bombing was the but viable tactic available to the USAAF at the fourth dimension given the failure of the precision bombing campaign.[172]

Later on the bombing, Emperor Hirohito toured the destroyed portions on xviii March.[173] Historians' views of the effects of this experience on him differ. F.J. Bradley states that the visit convinced Hirohito that Nippon had lost the war.[173] Tillman has written that the raid had no effect on the Emperor, and Frank argues that Hirohito supported continuing the war until mid-1945.[174] [175]

References [edit]

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ Equally the B-29's engines experienced less strain when flying at low altitudes, they required less fuel. The resultant weight savings allowed them to carry a larger bomb load.[40]

- ^ General Shizuichi Tanaka was the commander of the Eastern District Army.[54]

Citations [edit]

- ^ "Legacy of the Peachy Tokyo Air Raid". The Japan Times. March 15, 2015. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ Werrell 1996, pp. 151–152.

- ^ a b Werrell 1996, p. 152.

- ^ Biddle 2015, pp. 495–496, 502, 509.

- ^ Frank 1999, p. 46.

- ^ Karacas 2010, p. 528.

- ^ Peattie 2001, pp. 115–121.

- ^ Tillman 2010, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e Wolk 2004, p. 72.

- ^ Craven & Cate 1953, p. 555.

- ^ Fedman & Karacas 2014, p. 964.

- ^ Fedman & Karacas 2012, pp. 318–319.

- ^ Searle 2002, p. 120.

- ^ Craven & Cate 1953, pp. 553–554.

- ^ Wolk 2004, p. 71.

- ^ Searle 2002, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Wolk 2010, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Downes 2008, p. 125.

- ^ Searle 2002, p. 115.

- ^ Craven & Cate 1953, pp. 610–611.

- ^ Frank 1999, p. 55.

- ^ Frank 1999, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Craven & Cate 1953, p. 621.

- ^ Downes 2008, p. 126.

- ^ a b Craven & Cate 1953, p. 564.

- ^ Craven & Cate 1953, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Craven & Cate 1953, p. 565.

- ^ Chicken & Cate 1953, pp. 569–570.

- ^ Craven & Cate 1953, pp. 572, 611.

- ^ Craven & Cate 1953, p. 611.

- ^ Craven & Cate 1953, pp. 572–573.

- ^ Searle 2002, p. 113.

- ^ Craven & Cate 1953, p. 573.

- ^ a b c d e f g Frank 1999, p. 17.

- ^ Searle 2002, p. 114.

- ^ Frank 1999, p. 62.

- ^ Ralph 2006, p. 516.

- ^ Kerr 1991, p. 155.

- ^ Craven & Cate 1953, p. 612.

- ^ Ralph 2006, p. 512.

- ^ Craven & Cate 1953, pp. 612–613.

- ^ a b c Craven & Cate 1953, p. 613.

- ^ Kerr 1991, p. 149.

- ^ a b c d Frank 1999, p. 64.

- ^ a b Dorr 2002, p. 36.

- ^ Werrell 1996, p. 153.

- ^ Dorr 2012, p. 224.

- ^ Dorr 2012, p. 22.

- ^ Crane 1993, p. 131.

- ^ Foreign Histories Partitioning, Headquarters, United States Army Nippon 1958, pp. 34, 43.

- ^ Foreign Histories Segmentation, Headquarters, United States Army Japan 1958, p. 72.

- ^ a b c d e Craven & Cate 1953, p. 615.

- ^ Foreign Histories Sectionalisation, Headquarters, United States Regular army Nihon 1958, pp. 33, 61.

- ^ Frank 1999, p. 318.

- ^ Zaloga 2010, p. fifteen.

- ^ a b c d e Frank 1999, p. 65.

- ^ Foreign Histories Division, Headquarters, United States Army Nippon 1958, p. 48.

- ^ Coox 1994, p. 410.

- ^ Zaloga 2010, pp. 23, 24.

- ^ Dorr 2012, p. 149.

- ^ Strange Histories Sectionalization, Headquarters, United States Army Nihon 1958, p. 43.

- ^ a b c Frank 1999, p. eight.

- ^ a b c Dorr 2012, p. 161.

- ^ Frank 1999, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Frank 1999, pp. four–v.

- ^ Frank 1999, p. vi.

- ^ Hewitt 1983, p. 275.

- ^ a b Craven & Cate 1953, p. 614.

- ^ Kerr 1991, pp. 151–152.

- ^ Fedman & Karacas 2012, p. 313.

- ^ Kerr 1991, p. 153.

- ^ Fedman & Karacas 2012, pp. 312–313.

- ^ Searle 2002, pp. 114–115, 121–122.

- ^ Dorr 2002, p. 37.

- ^ Werrell 1996, p. 162.

- ^ a b Werrell 1996, p. 159.

- ^ Tillman 2010, pp. 136–137.

- ^ a b Frank 1999, p. 3.

- ^ Tillman 2010, p. 149.

- ^ Werrell 1996, p. 160.

- ^ a b Frank 1999, p. 4.

- ^ Tillman 2010, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Tillman 2010, p. 151.

- ^ a b Frank 1999, p. xiii.

- ^ a b Tillman 2010, p. 152.

- ^ a b Frank 1999, p. 66.

- ^ Edoin 1987, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Edoin 1987, p. 58.

- ^ a b Foreign Histories Division, Headquarters, United States Army Japan 1958, p. 73.

- ^ a b c d Craven & Cate 1953, p. 616.

- ^ Frank 1999, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Dorr 2012, p. 150.

- ^ a b Coox 1994, p. 414.

- ^ a b Frank 1999, p. 67.

- ^ a b c d e f Craven & Cate 1953, p. 617.

- ^ Hoyt 1987, p. 384.

- ^ a b c Frank 1999, p. 9.

- ^ a b Selden 2009, p. 84.

- ^ a b State highway 2016, p. 1052.

- ^ Edoin 1987, p. 77.

- ^ Edoin 1987, p. 63.

- ^ a b Frank 1999, p. 111.

- ^ Edoin 1987, p. 78.

- ^ Crane 2016, p. 175.

- ^ a b c Hewitt 1983, p. 273.

- ^ Crane 1993, p. 132.

- ^ a b Frank 1999, p. 10.

- ^ Hewitt 1983, p. 276.

- ^ Frank 1999, p. 12.

- ^ Kerr 1991, p. 191.

- ^ a b Superhighway 2016, p. 1054.

- ^ a b Hoyt 1987, p. 385.

- ^ Edoin 1987, p. 119.

- ^ Edoin 1987, p. 126.

- ^ Selden 2009, p. 85.

- ^ Masahiko 2011.

- ^ a b Karacas 2010, p. 522.

- ^ Kerr 1991, p. 203.

- ^ Edoin 1987, p. 106.

- ^ Frank 1999, p. xvi.

- ^ Tillman 2010, pp. 154, 157.

- ^ Kerr 1991, p. 208.

- ^ Edoin 1987, p. 110.

- ^ Kerr 1991, p. 205.

- ^ Bradley 1999, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Dower 1986, p. 41.

- ^ Crane 2016, p. 215.

- ^ Ralph 2006, pp. 517–518.

- ^ Ralph 2006, p. 521.

- ^ Ralph 2006, pp. 519–521.

- ^ a b Haulman 1999, p. 23.

- ^ Frank 1999, p. 69.

- ^ Lardas 2019, p. 52.

- ^ Kerr 1991, p. 210.

- ^ Frank 1999, p. 18.

- ^ Kerr 1991, p. 211.

- ^ Lucken 2017, p. 123.

- ^ Lucken 2017, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Lucken 2017, p. 124.

- ^ Crane 2016, pp. 175–176.

- ^ Edoin 1987, pp. 122–126.

- ^ Zaloga 2010, p. 54.

- ^ Zaloga 2010, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Craven & Cate 1953, p. 656.

- ^ Haulman 1999, p. 24.

- ^ a b Haulman 1999, p. 25.

- ^ Chicken & Cate 1953, p. 639.

- ^ Karacas 2010, pp. 522–523.

- ^ Rich, Motoka (March nine, 2020). "The Man Who Won't Let the World Forget the Firebombing of Tokyo". The New York Times . Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ Karacas 2010, p. 523.

- ^ a b Karacas 2010, p. 532.

- ^ Karacas 2010, pp. 521, 532.

- ^ "Center of the Tokyo Raids and War Harm". Center of the Tokyo Raids and War Impairment. Retrieved Apr 19, 2019.

- ^ "Mortiferous WWII U.Southward. firebombing raids on Japanese cities largely ignored". The Japan Times. AP. March 10, 2015. Retrieved Baronial 12, 2018.

- ^ a b c Munroe, Ian (March 11, 2015). "Victims seek redress for 'unparalleled massacre' of Tokyo air raid". The Nihon Times . Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- ^ Karacas 2011.

- ^ Chicken & Cate 1953, p. 623.

- ^ Biddle 2015, p. 521.

- ^ Lardas 2019, p. 88.

- ^ Crane 1993, p. 133.

- ^ Werrell 1996, p. 150.

- ^ Biddle 2015, p. 523.

- ^ Ralph 2006, pp. 520–521.

- ^ Tillman 2010, p. 260.

- ^ Hastings 2007, p. 319.

- ^ Crane 1993, p. 159.

- ^ Crane 2016, p. 212.

- ^ Selden 2009, p. 92.

- ^ Grayling 2006, p. 272.

- ^ Werrell 1996, p. 158.

- ^ Frank 1999, p. 336.

- ^ Tillman 2010, p. 263.

- ^ a b Bradley 1999, p. 36.

- ^ Tillman 2010, p. 158.

- ^ Frank 1999, p. 345.

Works consulted [edit]

- Biddle, Tami Davis (2015). "Anglo-American strategic bombing, 1940–1945". In Ferris, John; Mawdsley, Evan (eds.). The Cambridge History of the Second World War. Book one: Fighting the War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 485–526. ISBN978-1-139-85596-9.

- Bradley, F. J. (1999). No Strategic Targets Left. Nashville, Tennessee: Turner Publishing Company. ISBN978-1-56311-483-0.

- Coox, Alvin D. (1994). "Air War Against Japan" (PDF). In Cooling, B. Franklin (ed.). Instance Studies in the Achievement of Air Superiority. Washington, D.C.: Center for Air Force History. pp. 383–452. ISBN978-1-4781-9904-5.

- Crane, Conrad C. (1993). Bombs, Cities, and Civilians: American Airpower Strategy in World War II. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN978-0-7006-0574-3.

- Crane, Conrad C. (2016). American Airpower Strategy in World State of war Two: Bombs, Cities, Civilians, and Oil. Lawrence, Kansas: Academy Press of Kansas. ISBN978-0-7006-2210-8.

- Chicken, Wesley; Cate, James, eds. (1953). The Pacific: Matterhorn to Nagasaki. The Army Air Forces in World War II. Volume V. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. OCLC 256469807.

- Dorr, Robert F. (2002). B-29 Superfortress Units of World State of war two. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN978-ane-84176-285-two.

- Dorr, Robert F. (2012). Mission to Tokyo: The American Airmen Who Took the War to the Heart of Japan. Minneapolis: MBI Publishing Company. ISBN978-0-7603-4122-3.

- Dower, John W. (1986). War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN0-571-14605-8.

- Downes, Alexander B. (2008). Targeting Civilians in War. Ithaca, New York: Cornell Academy Press. ISBN978-0-8014-5729-half-dozen.

- Edoin, Hoito (1987). The Night Tokyo Burned. New York City: St. Martin's Press. ISBN0-312-01072-9.

- Fedman, David; Karacas, Cary (2012). "A cartographic fade to black: mapping the destruction of urban Japan during Earth State of war II". Journal of Historical Geography. 38 (3): 306–328. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2012.02.004.

- Fedman, David; Karacas, Cary (May 2014). "The Eyes of Urban Ruination: Toward an Archaeological Arroyo to the Photography of the Nippon Air Raids". Journal of Urban History. 40 (v): 959–984. doi:10.1177/0096144214533288. S2CID 143766949.

- Foreign Histories Division, Headquarters, United states Army Japan (1958). Japanese Monograph No. 157: Homeland Air Defense Operations Record. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Chief of Armed services History, Department of the Regular army. OCLC 220187679.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors listing (link) - Frank, Richard B. (1999). Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire. New York Metropolis: Penguin Books. ISBN0-fourteen-100146-ane.

- Grayling, A.C. (2006). Among the Expressionless Cities: Was the Allied Bombing of Civilians in WWII a Necessity or a Crime?. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN978-0-7475-7671-6.

- Hastings, Max (2007). Nemesis: The Boxing for Japan, 1944–45. London: HarperPress. ISBN978-0-00-726816-0.

- Haulman, Daniel L. (1999). Hitting Home: The Air Offensive Confronting Japan (PDF). The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War Two. Washington, D.C.: Air Forcefulness Historical Studies Office. ISBN978-one-78625-243-2.

- Hewitt, Kenneth (1983). "Place Anything: Area Bombing and the Fate of Urban Places". Annals of the Clan of American Geographers. 73 (2): 257–284. doi:ten.1111/j.1467-8306.1983.tb01412.x. JSTOR 2562662.

- Hoyt, Edwin P. (1987). Japan'south War: The Smashing Pacific Conflict. London: Arrow Books. ISBN0-09-963500-3.

- Karacas, Cary (2010). "Place, Public Retentivity and the Tokyo Air Raids". The Geographical Review. 100 (iv): 521–537. doi:x.1111/j.1931-0846.2010.00056.x. S2CID 153372067.

- Karacas, Cary (January 2011). "Fire Bombings and Forgotten Civilians: The Lawsuit Seeking Bounty for Victims of the Tokyo Air Raids". The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus. 9 (3).

- Kerr, E. Bartlett (1991). Flames Over Tokyo: The U.South. Army Air Forcefulness's Incendiary Campaign Confronting Japan 1944–1945. New York City: Donald I. Fine Inc. ISBNi-55611-301-3.

- Lardas, Marker (2019). Japan 1944–45: LeMay's B-29 Strategic Bombing Campaign. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN978-1-4728-3246-7.

- Lucken, Michael (2017). The Japanese and the War: Expectation, Perception, and the Shaping of Memory. New York Urban center: Columbia Academy Press. ISBN978-0-231-54398-9.

- Masahiko, Yamabe (January 2011). "Thinking At present about the Great Tokyo Air Raid". The Asia-Pacific Journal: Nihon Focus. 9 (3).

- Peattie, Mark R. (2001). Sunburst: The Rise of Japanese Naval Air Power, 1909–1941. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Printing. ISBN978-ane-59114-664-3.

- State highway, Francis (2016). Hirohito'due south State of war: The Pacific War, 1941–1945. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN978-1-4725-9671-0.

- Ralph, William Westward. (2006). "Improvised Destruction: Arnold, LeMay, and the Firebombing of Japan". War in History. 13 (four): 495–522. doi:10.1177/0968344506069971. S2CID 159529575.

- Searle, Thomas R (January 2002). ""Information technology Made a Lot of Sense to Impale Skilled Workers": The Firebombing of Tokyo in March 1945". The Periodical of Military History. 66 (1): 103–133. doi:10.2307/2677346. JSTOR 2677346.

- Selden, Mark (2009). "A Forgotten Holocaust: U.S. Bombing Strategy, the Devastation of Japanese Cities, and the American Way of State of war from the Pacific War to Iraq". In Tanaka, Yuki; Young, Marilyn B. (eds.). Bombing Civilians: A Twentieth-Century History. New York: New Press. pp. 77–96. ISBN978-1-59558-363-5.

- Tillman, Barrett (2010). Whirlwind: The Air War Against Nihon 1942–1945. New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN978-1-4165-8440-7.

- Werrell, Kenneth P. (1996). Blankets of Burn: U.S. Bombers over Japan during Earth War II. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Printing. ISBN1-56098-665-four.

- Wolk, Herman Southward. (April 2004). "The Twentieth Against Nihon" (PDF). Air Force Magazine. pp. 68–73. ISSN 0730-6784.

- Wolk, Herman S. (2010). Cataclysm: General Hap Arnold and the Defeat of Japan. Denton, Texas: University of Northward Texas Press. ISBN978-ane-57441-281-9.

- Zaloga, Steven J. (2010). Defense force of Nippon 1945. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN978-1-84603-687-3.

Farther reading [edit]

- Hoyt, Edwin P. (2000). Inferno: The Firebombing of Japan, March 9 – August 15, 1945. Lanham, Maryland: Madison Books. ISBNone-56833-149-5.

- Neer, Robert M. (2013). Napalm: An American Biography . Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN978-0-674-07301-2.

douglaswhinevesock.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bombing_of_Tokyo_%2810_March_1945%29

0 Response to "Operation Meetinghouse Do It Again Lemay"

Post a Comment